Introduction

A set of nation-wide sources have been used to provide an overview of the settlements at key points in time. There are many sources to use when plotting the fortunes of settlements, mainly focusing on the variety of taxation documents that were composed for the central government. The ones chosen for the main database entries are those that cover the majority of the country and hence provide a near-complete view. These start with the Domesday Book compiled in 1086, and follow with a taxation of ecclesiastical income in 1291, the Lay Subsidy taken in 1344, Poll Taxes in 1377, 1379 and 1381, Lay Subsidies in 1524, 1525 and 1543, a record of number of households in each diocese in 1563 and the Census of 1801 and 1841. Each of these provides different information – some the number of the taxable people, some the taxable amount payable by a settlement or area, or the number of households, but not a total population at any settlement. They do, however, allow a relative indication of settlement size across the country. As with all historical sources, these records although carried out nation-wide, do not always have a complete record. Some areas were exempt from taxation for a number of reasons, some records have not survived down to the modern era, and some places are hidden in the record by the way they were recorded. For every county a summary of the availability of these records is given from a link on the county page. Many other taxation records do exist on a county basis and these are mentioned in separate village descriptions.

Below is a description of all the records used in this section of the website.

Domesday Book

Introduction

There are several different transcriptions of the Domesday Book. The one that has been used by the website is that published by Philimore. This is available as printed-copy but it has also been digitised by the Domesday Book Project (see http://www.domesdaybook.net/).

The Domesday Book was compiled on the order of William I in 1086. The data in the Domesday Book are recorded by landowner, then manor. As the basic unit of measurement, the manor was never defined in the Domesday record. It does not directly equate to a settlement, but more to a unit of land, however it is linked to the vill (village) in which it was located. The result is that each vill may constitute part of several different manors, and therefore have more than one record in Domesday. These separate manors within the same vill may also have a number of different landowners. Land in outlying areas may also be included under the name of the manor to which it is attached. This can mean that land and people may be recorded as located in one particular area but might actually be located at a distance. Land under one entry within Domesday may also record several vill names.

The main unit of measurement used in the Domesday Book as a whole was the hide. The Saxon hide was a theoretical unit of land required to support a family farmstead, but by the Late Saxon period, it had become a unit of taxation and hence was a fiscal unit rather than signifying an area of land. In the old area of Danelaw the measurements are given in carucates, the Danelaw equivalent to the hide. A hide had become a unit of taxation by the time of Domesday, and bears little relationship to an area of land.

A number of different aspects of the landholding were recorded in the survey. These include the number of ploughlands and a formula referred to as ‘land for x ploughs’. The ‘land for x ploughs’ provides us with a figure of the agricultural potential of the manor, although the actual amount of land that was farmed may be different.

Other resources recorded at Domesday include population. The population of each manor is recorded as numbers of different classes of population which does vary in terminology and meaning in different regions. Villagers are equivalent to villeins, freemen are equivalent to sokemen and smallholders to bordars in other translations. Other forms of population recorded include burgesses, cottagers, slaves and priests. Also recorded in Domesday are resources such as mills, meadow, wood, woodland pasture, underwood, marsh, saltpans, livestock, fisheries etc.

There has been much debate over the nature of the record presented by Domesday. For instance, the record can hide or omit settlement and population; it has been noted that the number of actual tenants in 1086 may in fact be 50% more than those recorded if a similar number of sub and joint tenancies were present in the late eleventh century as are recorded for the thirteenth (Postan 1972). Nevertheless, Domesday provides a region-wide record taken at a specific point in time which can be used to assess the extent, if not the true nature, of settlement in the eleventh century.

Database contents

Two items are recorded in this database: a reference to the entries in the Domesday Book Phillimore editions, and the minimum number of individuals that are recorded as belonging to that manor. The data for these sections were derived from the Domesday Explorer Project which was based at the University of Hull.

The Phillimore county editions number each of the entries in the record with a coding system. Each county edition is divided into the respective landowners, with the first (usually the King) given the number 1, and the second landowner, 2 etc. For each entry under a particular landowner, the entries are given separate numbers. So entry 2,5 would be landowner 2 and entry 5. This form of notation has been used by the website so people can be directed straight to the entry or entries about a particular manor. These details can be found in the printed versions or via the web link to the databases at the University of Hull. The Phillimore entry is prefixed with a county code to identify which county record should be used (see Glossary for a list of county codes).

A total population figure for a manor was calculated based on the number of villagers, freemen, smallholders, cottagers, slaves, burgesses and priests. The total for each settlement has been calculated from the individual manors with the same settlement name recorded under different landowners in the Domesday Book.

For each site that has a Domesday record a direct link is provided to the Open Domesday site that provides a summary of the information.

Further Information

Domesday Explorer Project – http://www.domesdaybook.net/

Open Domesday – https://opendomesday.org/

Hull University Repository – https://www.hull.ac.uk/choose-hull/study-at-hull/library/resources/domesday-dataset

Postan, M.M. 1972. The Medieval Economy and Society. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

1291 Taxatio or Taxatio ecclesiastica Angliae at Walliae, auctoritate P. Nicholai IV

Introduction

A papal tax was granted to Edward I by Pope Nicholas IV in 1291 to help pay for a crusade at a rate of a tenth of all ecclesiastical income (Denton 1993). The tax was on spiritual income which included monies from tithe and glebe land. The only monastic orders exempt from the tax were the Templars and the Hospitallers. Benefices were assessed with an income threshold of four pounds, but the full nature of the monies that were assessed is unclear (Denton 1993). The Taxatio does, however, provide some indication of the wider agricultural wealth of an area as tithes were included within the valuation.

A full copy of the 1291 Taxatio does not survive, but as it formed the basis for later taxes, missing portions can be substituted with other documentation (Denton 1993). The Taxatio records the amount payable by the individual churches, and vicarages attached to the church, and the amount payable on any pension or portion. The pension or portion was usually payable by the church to a monastic house in return for the lease of tithes which belonged to the house, but on many occasions it appears that a fixed sum was paid for a permanent transfer of the tithes (Denton 1993).

Database contents

The dataset has been compiled from the Taxatio database produced by the University of Manchester (https://www.dhi.ac.uk/taxatio/), which was created from the text version of the Taxatio published by Caley (1802). As with this publication, the database only considers the assessment of spiritualities. Caley’s (1802) work was a compilation of information from a number of different sources, mainly fifteenth century Exchequer books. Any of the values recorded have been converted to pence within the dataset. There are two entries – firstly the main one, usually the parish church, and a further one that lists all other pensions and portions, and to whom they were payable. The record is not complete for the whole country.

Further Information

Taxation website https://www.dhi.ac.uk/taxatio/

Caley, J. 1802. Taxatio Ecclesiastica Angliae et Walliae, auctoritate P. Nicholai IV, circa A.D. 1291. London.

Denton, J. 1993. ‘The Valuation of the Ecclesiastical Benefices of England and Wales’, Historical Research 66: 232-50.

Lay Subsidy of 1334

Introduction

The Lay Subsidy of 1334 records one of the special taxes granted by Parliament to the Crown to help with the extra expenses incurred arising from continued troubles with France and Scotland (Glasscock 1975). The tax was upon personal wealth, the value of an individual’s movable goods rather than their land and buildings, and was applied only to the laity (Glasscock 1975). Different payment fractions occurred in different subsidies, but that for the 1334 subsidy was levied at a fifteenth of the value from rural areas and as a tenth of the value from the boroughs and areas of ancient demesnes (Glasscock 1975). This followed not long after a 1332 tax which used the same fractions, but the 1334 tax differed in the fact that the sum paid was a figure that was agreed on by the local community involved. The amount could not be less than that paid in 1332 and was negotiated between the community and the appointed tax officials (Glasscock 1975).

Many subsequent taxes were based on the 1334 figures, and so lose their value in assessing any changes that have occurred in the population; as Glasscock (1975: xvi) notes: ‘within a very short time the tax ceased to bear any direct relationship to the lay wealth and taxable capacity of the country’. However, due to the fact that any gaps in the 1334 record can be filled by any subsequent records that were based on the 1334 tax, this lay subsidy is one of the most complete records of taxation from the fourteenth century for the country as a whole. There were a number of items that were not taxable in the 1334 subsidy, including clerical property that was included in the 1291 taxation of Pope Nicholas, as well as locally argued exemptions, mainly relevant to the Cinque Ports (Glasscock 1975). Although this record does not provide population numbers, or exact wealth, it provides an overview of possible surplus wealth of the region in the fourteenth century and can be used to compare the fortunes of different settlements.

Database contents

The tax was recorded in pounds, shillings and pence for each township, and this has been converted into a pence equivalent for direct comparison between settlements. All the references have been taken from Glassock’s 1975 publication of the subsidy.

Further Information

Glasscock, R.E. 1975. The Lay Subsidy of 1334. London: British Academy.

Poll Taxes of 1377, 1379 and 1381

Introduction

During the later fourteenth century, fifteenths and tenths (subsidies) were still collected as in 1334, but experiments took place at attempting to tax individuals rather than their wealth. The Poll Tax of 1377 introduced a per capita levy, which was to be repeated in 1379 and 1381, although by this time the old habits were returning, with the collectors instructed to base the amount collected on the wealth of the individuals (Fenwick 1998). The 1377 Poll Tax was collected from every layman and woman over the age of fourteen who was not a mendicant, at a rate of one groat (fourpence) (Fenwick 1998). The Poll Tax of 1379 introduced a scale of payments from fourpence to ten marks, to be collected from every lay married and single man and every single woman over the age of sixteen (Fenwick 1998). The Poll Tax of 1381 was collected from every lay man and woman of fifteen years and over at a rate of three groats (one shilling), but in order that the rich should help the poor, everyone was ‘charged according to his means’, with the resulting total number of shillings from any one vill being equivalent to the number of taxpayers (Fenwick 1998: xvi). The clergy were exempt from the Parliamentary taxes, although there was an attempt to remove the other exemptions that had previously existed for the lay subsidies, but with varying degrees of success (Fenwick 1998).

The Poll Tax of 1377 did not require detailed records to be kept of individuals who were taxed; only the numbers of individuals and the amount due were noted, but more detailed records were kept for the taxes of 1379 and 1381 (Fenwick 1998).

Database contents

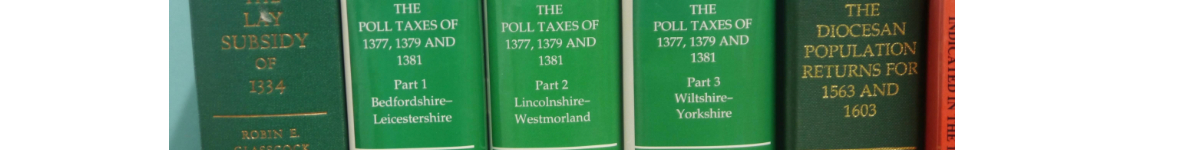

The survival of the poll tax documents varies across the country. The database therefore includes all three taxes – 1377, 1379, and 1381 in order to show as much of the available data as possible. Two values are recorded – the number of individuals taxed and the total amount. To provide a comparison with the other datasets, the taxation payable in pounds, shillings and pence has been converted into pence. All the data have been derived from the three volumes published by Caroline Fenwick (Fenwick 1998, 2001, 2005).

Further Information

Fenwick, C.C. 1998. The Poll Taxes of 1377, 1379 and 1381, Part 1, Bedfordshire-Lincolnshire. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fenwick, C.C. 2001. The Poll Taxes of 1377, 1379 and 1381, Part 2, Lincolnshire-Westmorland. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fenwick, C.C. 2005. The Poll Taxes of 1377, 1379 and 1381, Part 3, Wiltshire-Yorkshire. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lay Subsidies of 1524, 1525 and 1543

Introduction

The collection of the rates as set down by the Lay Subsidy of 1334 continued until 1623 and became known as ‘the fifteenth’ (Hoyle 1994). During the Tudor period the lay subsidy was revived, running alongside that of the fifteenth. This new subsidy was based on either income from land, other income, or goods or wages, with each payee only being taxed on one category (Hoyle 1994). Early records of the Tudor lay subsidies contain little information on the amounts taxed at certain villages – they only show the amount collected by different tax collectors. In 1523 an act was passed allowing four lay subsidy payments in the subsequent years. The records were expanded to include information on which towns, parishes or other taxation unit had provided which amount. As such, in the first payment of the four in 1524, the information on individual taxpayers was included (Hoyle 1994, Sheail 1998a). The subsidies of 1524 and 1525 recorded every man who was worth more than £1. The later two surveys changed the criteria to men who earned more than £50 in a year (in 1526) and those who were rich in moveable goods (in 1527). The rates at which individuals were taxed depended on a number of factors, shown below.

1s in the pound Annual income of land and other sources

1s in the pound Capital value of moveables worth £20 and upward

6d in the pound Capital value of moveables worth £2 and upward to £20

4d in the pound Capital values worth £1 and under £2

4d paid Those aged 16 years and above and who earned wages of and in excess of £1 a year

The records for the 1524/25 subsidies are one of the most complete and useful surveys, and Sheail (1998a, 1998b) has attempted to produce calculations from the different surveys of the period to provide combined figures for individual vills. As with all the tax records, there are numerous problems using the data, such as the omission of much of the clergy and those valued at under £1, but as Sheail (1998a: 36) concludes, the study of the survey of specific counties and hundreds overcomes some of the issues as ‘they were surveyed by the same men and consequently have a greater degree of uniformity’.

Database contents

The figures used within this research are those provided in Sheail (1998b), which presents the total collected from the individual vills and the number of people that were taxed. As with other taxes, the total paid has been converted to pence. For a number of counties Sheail also presents the figures from subsidies in the 1540s (from 1543, 1544 or 1545) but only the number of people assessed, not the amount of money requested. Although this later survey has often been cited as being superior to the earlier 1524/25 surveys, the record is not complete and is much damaged (Sheail 1998a).

Further Information

Hoyle, R. 1994. Tudor Taxation Records: a guide for users. London: PRO Readers’ Guide 5.

Sheail, J. 1998a. The Regional Distribution of Wealth in England as Indicated in the 1524/5 Lay Subsidy. Volume 1. London: List and Index SocietySpecial Series 28.

Sheail, J. 1998b. The Regional Distribution of Wealth in England as Indicated in the 1524/5 Lay Subsidy. Volume 2. London: List and Index Society Special Series 29.

Diocesan Returns of 1563

Introduction

The Privy Council commanded in 1563 that every bishop should provide an outline of the administrative structure of their dioceses including a list of the number of households in every village and hamlet in each parish (Dyer and Pallister 2005). It is not fully understood why these data were required but suggestions include the idea of quantifying the number of potential almsgivers available for contribution to poor relief (Dyer and Pallister 2005).

Although all 26 dioceses returned an initial report of the administrative structures, they did not have to reply instantly with the number of households. So unfortunately some returns have only survived in partial form and have no lists of households available. Only 12 dioceses have the list of households surviving, and it has been suggested that the missing ones were lost en masse at some point in the past (Dyer and Pallister 2005). Records survive for Bath and Wells, Canterbury, Carlisle, Chester, Coventry and Litchfield, Durham, Ely, Gloucester, Lincoln and Worcester as well as the Welsh dioceses of Bangor and St David’s. There are no records of households from Bristol, Chichester, Exeter, Hereford, Llandaff, London, Norwich, Oxford, Peterborough, Rochester, St Asaph, Salisbury, Winchester and York.

As with all such records there are instances of rounding of numbers, errors in copying and other general issues. Tests of comparison with other localised records of households from around the same period show a surprising similarity which confirms the usefulness of these records (Dyer and Pallister 2005).

Database contents

The figures used by the database are those published by Dyer and Palliser (2005). It simply records the number of households recorded in each parish or settlement.

Further Information

Dyer, A. and D.M. Palliser 2005. The Diocesan Population Returns for 1563 and 1603. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Census population 1801

Introduction

This was the first national census of its kind in Britain and established the way forward for a ten yearly record of the nature of the population of Britain from that time forward. The need for a census was justified on a number of different levels including food shortage and the need to find people to fight wars (Levitan 2011). In essence it could be viewed as a governmental project for control and management, but Levitan also draws attention to it as a tool that built identity and nationhood (Levitan 2011). The first census in 1801 was to be taken on 20th January, but there was little notice or time to prepare so many returns which came in late. Each Overseer of the Poor in a parish had to compile the statistics and send them in. They were required to provide the number of inhabited houses in the parish, by how many families they were occupied, the number of uninhabited houses, the numbers of males and females, and the total population. There were some exceptions including men in the army, the navy, or the militia, and merchants on registered vessels. There were also requests for information on different categories of employment. Not all parishes sent in the requested information so the record is not complete. Some of the requests had caused confusion and these issues were ironed-out in future census requests.

Database contents

The source of data for this website has been the 1801 Census report which is available online from Histpop – The Online Historical Population Reports Website – www.histpop.org. The data are from the enumeration abstract which was prepared on a county basis, then divided into hundreds. The database records the total population recorded. This may be associated with a single settlement, or a parish. The type of unit is recorded after the total, whether it is a parish, extra-parochial, a hamlet, tithing or township. For a discussion on the definition of these terms see the section on villages. It must be noted that if a parish total is recorded it may include a number of different settlements.

Further Information

Higgs, E. 1989. Making Sense of the Census. London: HMSO.

Levitan, K. 2011. A Cultural History of the British Census. New York: Palgrave.

Census population 1841

Introduction

Since 1801 a census of Great Britain had been undertaken every 10 years. By the late 1830s the use of the information by statisticians had increased and many refinements were made to the process to increase the clarity and value of the data collected (Levitan 2011). Numerous extra elements were also required in the 1841 Census which lengthened the entire process of compiling and extracting the data. Another innovation for the 1841 Census was that every head of household was required to complete the information, whereas earlier surveys were compiled centrally in the parish. Compared to the 1801 Census, there was a greater amount of detail given in the accompanying footnotes, and these may actually identify smaller settlements that were not mentioned in the main text of the report or in 1801.

Database contents

The source of data for this website has been the 1841 Census report which is available online from Histpop – The Online Historical Population Reports Website – www.histpop.org. The data are from the enumeration abstract which was prepared on a county basis, then divided in hundreds. The database records the total population recorded and the number of inhabited houses. These may be associated with a single settlement, or a parish. The type of unit is recorded after the total, whether it is a parish, extra-parochial, a hamlet, tithing or township. For a discussion on the definition of these terms see the section on villages. It must be noted that if a parish total is recorded it may include a number of different settlements.

Further Information

Higgs, E. 1989. Making Sense of the Census. London: HMSO.

Levitan, K. 2011. A Cultural History of the British Census. New York: Palgrave.

E179 date and type of last document

Introduction

E179 is the title given to a series of records in the National Archives. It is also titled the Exchequer: King’s Remembrancer: Particulars of Account and other records relating to Lay and Clerical Taxation. It holds a wealth of tax records relating to England between 1190-1690. It includes the 1334 Lay Subsidy, the fourteenth-century poll taxes and the sixteenth-century lay subsidies used by this website. In total the archive contains over 30,000 items including bundles, files and rolls. A searchable database of these records on place-name is available. This does not provide the entry for that settlement, but the type of document and its location in the record. As these data include the date of the assessment, it does allow an indication of when a settlement disappeared from the taxation record. This may not indicate that a settlement had become deserted but does give an indication of declining taxable wealth. On many occasions the last date of record may just indicate the last available record in E179 in the late-seventeenth century. It must also be noted that some taxation is not based on settlements but on parish areas, which may include many other settlements.

Database contents

The database lists the date and nature of the last record for the settlement. This is copied directly from the E179 database.

Further Information

National Archives http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/e179/