Description

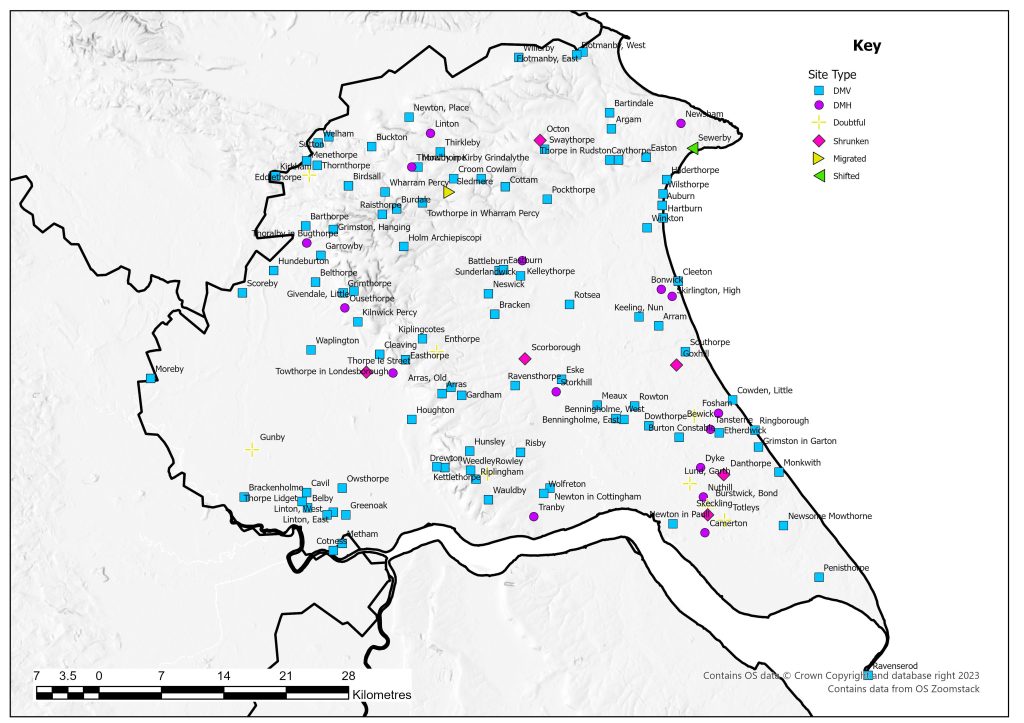

Yorkshire was one of the counties to have separate lists of deserted villages produced in the early years of study, with the list for the East Riding appearing in 1952 (Beresford 1952). As such in 1954 Beresford only published some of the key sites ‘intended as a guide for visitors’ (Beresford 1954: 392). The 1952 list noted 123 sites, although in the introduction Beresford hints at 99 (Beresford 1952:44). He suggests that around 40-50 were a result of sheep farming depopulations and 20-30 were earlier desertions due to the Black Death (Beresford 1952: 4). A number of settlements had also been lost through coastal erosion. By 1968 the number of settlements had risen slightly to 129, with three of the 1952 listing having disappeared in the meantime. The East Riding of Yorkshire has remained a focus for attention, with the research project at Wharram Percy being a catalyst for other studies elsewhere. The continued investigation of medieval settlement in the area has resulted in the increase of known sites and the listing of many shrunken settlements. Research has included detailed local studies. One of the key examples of this is the PhD thesis of Susan Neave that looked at settlement contraction during the seventeenth and eighteenth century, with particular examples from the Bainton Beacon division of the county (Neave 1990). This revealed that many of the ‘classic’ deserted settlements of this area such as Rotsea and Sunderlandwick were late depopulations and that for many villages the end was a long drawn-out process. Also new forms of evidence occasionally appear which allow clearer pictures to be painted of settlements and their road to desertion. A recently discovered survey from 1723 of the village of Menethorpe has allowed the pre-desertion settlement to be viewed in new light and the final desertion of the village to be placed in 1872 (Cookson 2010-2011).

The landscape of the East Riding is characterised by nucleated settlements and this is one of the reasons why we see so many villages initially identified in the county as the picture was much clearer than areas of dispersed settlement. There have been numerous studies of settlement development in the different zones of the East Riding with ideas of planning in village design and the origins of open field systems (e.g. Harvey 1980, 1982, Sheppard 1976).

Excavations

For information on the long-term project at Wharram Percy please look under the Beresford pages of this website as this provides a summary of the work undertaken between 1950-1990 as well as the more recent topographic and geophysical survey. It also discusses the impact this project had on a generation of archaeologists.

However Wharram is not the only site to be investigated in the county. Numerous excavations have been carried out, some on a small scale and never reported such as at Auburn and Wauldby. Other small projects have included that at Arras, were fieldwork in 2004-05 to the west of the farm found a large quantity of pottery dating from the twelfth to fifteenth centuries (Phillpott 2005). It also potentially located the position of the chapel.

At Hilderthorpe, to the south of Bridlington, an excavation on the main street in 1954-5 found a fifteenth-century pot sherd in a re-cut and sealed ditch, confirming that the street was in use in the medieval period. Other features uncovered included a number of walls from toft boundaries and possible buildings (Brewster et al. 1975).

The site at Riplingham can be clearly seen from with road. A hollow way runs east-west with crofts and tofts to the north and south. Excavations in 1956-57 were undertaken to the west of Riplingham House. The first house excavated was found to date from the late fifteenth or early sixteenth with phases of reconstruction up to the middle of the eighteenth century (Wacher 1966). The second house excavated was built in the thirteenth century and rebuilt twice before becoming completely ruined in the late fourteenth century (Wacher 1966). A further house site was excavated in 1966 (Wilson and Hurst 1967).

At Cowlam, a rescue excavation was conducted in 1971-2 in advance of ploughing, uncovering a croft containing two seventeenth-century house sites and finds dating from the thirteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, although this must represent only a snippet of the village’s history. A field visit in 1975 still found discernable earthworks in the north whilst the southern parts had been ploughed. By the late 1990s air photographs show the whole site to have been ploughed level, albeit that some features are still visible as cropmarks. AWAITING COPY OF ARTICLE

A number of sites have also under gone detailed historic and topographic survey. The earthworks at Rotsea were surveyed in 1989 and the plan published in the same year, with a larger scale plan appearing in 1990 (Cocroft 1989, 1990). The main hollow way takes two routes and it is suggested that they be could be different phases with the more sinuous route replaced at a later date (Cocroft 1989). The survey and combined documentary evidence has shown that the nucleated medieval village became reduced to a number of substantial farms and was finally deserted with dispersed farms being developed. It is suggested that the change from village to individual farms came about by the early sixteenth century possibly with the conversion to pasture. A map of 1784 shows the settlement had been completely depopulated by this time (Neave 1990). The research undertaken at Eske shows how the physical remains can be matched to the documentary evidence (English and Miller 1991). This showed the replanning of the site which occurred in 1300. Field walking produced a range of thirteenth to sixteenth-century pottery, but all the later fifteenth-century sherds were fine tablewares indicating that just the leading tenants remained in residence. A north-south street with a number of tofts and sunken yards is visible. The tofts to the east of the hollow way appear to have no crofts. To the south of this area is an east-west hollow way leading to the River Hull. This is suggested as the original focus of the settlement with the area to the north as a planned expansion sometime before the late thirteenth century (English and Miller 1991).

County Boundaries

Until 1974 there had only been a few changes to the boundary of the East Riding, with loses to the West Riding. With reorganisation, for a while East Riding disappeared, replaced by Humberside. In 1996 with the return of the East Riding it became much smaller in scale and parts of the north of the county are now within North Yorkshire. The City of Kingston upon Hull is also its own Unitary Authority.

Documentary Evidence

The Domesday record for Yorkshire is complex. Many land holdings are listed in groups so disentangling individual populations is difficult. Thus although the record may show a large population, this could be spread between many different land holdings with no clear way of distinguishing which belong to a particular place.

The 1334 record is not complete but has been supplemented with the 1344 Lay Subsidy (Glasscock 1975). There are a number of complex records with settlements being recorded in two separate areas. This issues continues with the 1377 Poll Tax with the record not clearly indicating whether the recorded tax is for the whole vill or part of a vill. In 1379 only one Wapentake has records (Howdenshire) and in 1381 there are records from three wapentakes (Fenwick 2005). For the lay subsidies of the 1520s there is clear evidence of underestimation of the value to be taxed and of avoidance, and cannot be compared with other regions (Sheail 1998: 184). The record for the 1540s does not survive for the whole county, and where it is used it is primarily the 1544 Subsidy, and in a few places from 1543. No Diocesan Returns survive for 1563 (Dyer and Palliser 2005).

County Records

Humber SMR covers the East Riding and City of Hull. Northern parts of the historic East Riding of Yorkshire fall with the North Yorkshire and City of York HERs. All are accessible via Heritage Gateway.

References

Beresford, M.W. 1952. ‘The Lost Villages of Yorkshire Part II’, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal 38: 44-70.

Beresford, M.W. 1954. The Lost Villages of England. London: Lutterworth.

Brewster, T.C.M., P. Armstrong and P. Hough 1975. ‘Excavations at Hilderthorpe’, East Riding Archaeologist 2: 71-81.

Cocroft, W.D., P. Everson and W.R. Wilson-North 1989. ‘The Deserted Medieval Village of Rotsea, Humberside’, Medieval Settlement Research Group 4: 14-17.

Cocroft, W.D., P. Everson and W.R. Wilson-North 1990. ‘Rotsea’. Medieval Settlement Research Group 5: 19-20.

Cookson, G. 2010-2011. ‘Menethorpe: Rediscovering a Lost Village’, The Rydale Historian 25: 22-31.

Dyer, A. and D.M. Palliser 2005. The Diocesan Population Returns for 1563 and 1603. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

English, B. and K. Miller 1991. ‘The Deserted Village of Eske, East Yorkshire’, Landscape History 13: 5-32.

Fenwick, C.C. 2005. The Poll Taxes of 1377, 1379 and 1381: Part 3: Wiltshire-Yorkshire. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Glasscock, R.E. 1975. The Lay Subsidy of 1334. London: Oxford University Press.

Harvey, M. 1980. ‘Regular Field and Tenurial Arrangements in Holderness, Yorkshire’, Journal of Historical Geography 6: 3-16.

Harvey, M. 1982. ‘Regular Open-Field Systems of the Yorkshire Wolds’, Landscape History 4: 29-39.

Neave, S. 1990. Rural Settlement Contraction in the East Riding of Yorkshire c. 1660-1760 with Particular Reference to the Bainton Beacon Division. University of Hull Unpublished PhD Thesis.

Phillpott, M. 2005. ‘A Landscape Study of a Deserted Medieval Settlement at Arras, East Yorkshire’, Medieval Settlement Research Group Annual Report 20: 31-33

Sheail, J. 1998. The Regional Distribution of Wealth in England as Indicated in the 1524/5 Lay Subsidy Returns: Volume One. London: List and Index Society.

Sheppard, J.A. 1976. ‘Medieval Village Planning in Northern England: Some Evidence from Yorkshire’, Journal of Historical Geography 2: 3-20.

Wacher, J. 1966. ‘Excavations at Riplingham East Yorkshire 1956-7’, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal 41:608-669.

Wilson, D. and D.G. Hurst 1967. ‘Medieval Britain in 1966’, Medieval Archaeology 11: 262-319.

List of deserted villages recorded in 1968

- Argam

- Arram

- Arras

- Arras, Old

- Auburn

- Barthorpe

- Bartindale

- Battleburn

- Belby

- Belthorpe

- Benningholme, East

- Benningholme, West

- Bewick

- Birdsall

- Bonwick

- Bracken

- Brackenholme

- Buckton

- Burdale

- Burstwick, Bond

- Burton Constable

- Camerton

- Cavil

- Caythorpe

- Cleaving

- Cleeton

- Cotness

- Cottam

- Cowden, Little

- Cowlam

- Croom

- Danthorpe

- Dowthorpe

- Drewton

- Dyke

- Eastburn

- Easthorpe

- Easton

- Eddlethorpe

- Enthorpe

- Eske

- Etherdwick

- Flotmanby, East

- Flotmanby, West

- Fosham

- Gardham

- Garrowby

- Givendale, Little

- Goxhill

- Greenoak

- Grimston in Garton

- Grimston, Hanging

- Grimthorpe

- Gunby

- Hartburn

- Hilderthorpe

- Holm Archiepiscopi

- Houghton

- Hundeburton

- Hunsley

- Keeling, Nun

- Kelleythorpe

- Kettlethorpe

- Kilnwick Percy

- Kiplingcotes

- Kirkham

- Linton

- Linton, East

- Linton, West

- Lund, Garth

- Meaux

- Menethorpe

- Metham

- Monkwith

- Moreby

- Mowthorpe

- Neswick

- Newsham

- Newsome Mowthorne

- Newton in Cottingham

- Newton in Paull

- Newton, Place

- Nuthill

- Octon

- Ousethorpe

- Owsthorpe

- Penisthorpe

- Pockthorpe

- Raisthorpe

- Ravenserod

- Ravensthorpe

- Ringborough

- Riplingham

- Risby

- Rotsea

- Rowley

- Rowton

- Scorborough

- Scoreby

- Sewerby

- Skeckling

- Skirlington, High

- Sledmere

- Southorpe

- Storkhill

- Sunderlandwick

- Sutton

- Swaythorpe

- Tansterne

- Thirkleby

- Thoralby in Bugthorpe

- Thoralby in Kirby Grindalythe

- Thornthorpe

- Thorpe in Rudston

- Thorpe le Street

- Thorpe Lidget

- Totleys

- Towthorpe in Londesborough

- Towthorpe in Wharram Percy

- Tranby

- Waplington

- Wauldby

- Weedley

- Welham

- Wharram Percy

- Willerby

- Wilsthorpe

- Winkton

- Wolfreton