Description

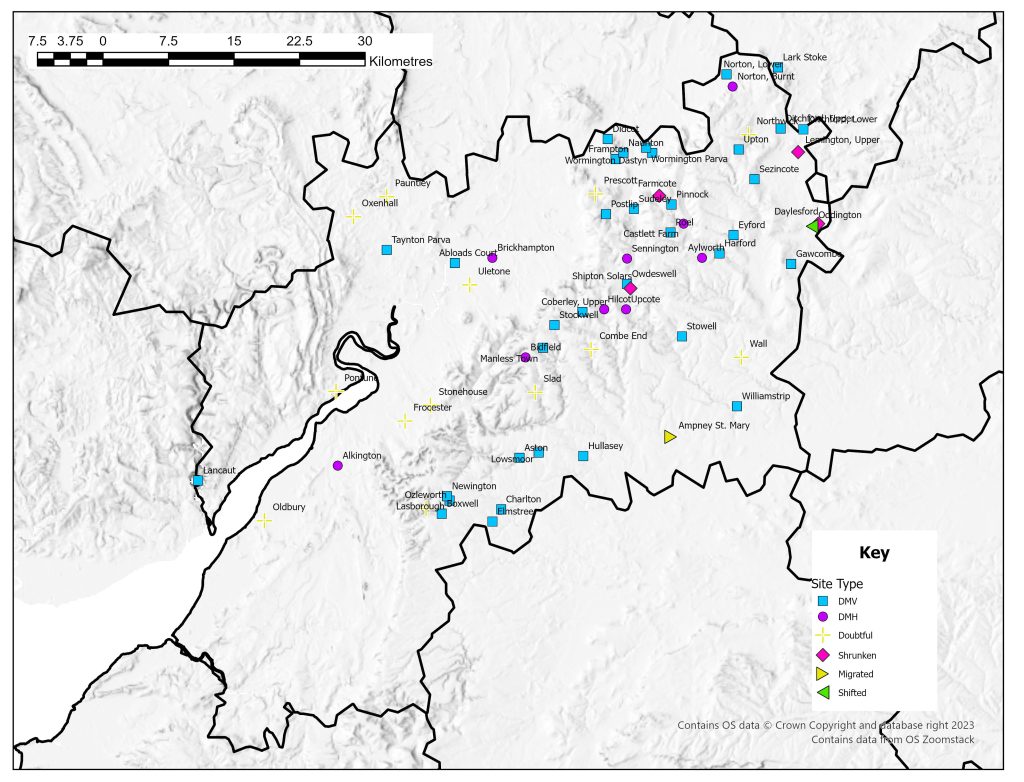

The compiling of a definitive list of deserted medieval settlements in Gloucestershire has seen many attempts. There are 15 sites mentioned by Beresford in 1954. A revised list of sites in 1959 contained 28 settlements (Icomb has been lost by this point) and a further revision in 1962 adds 26 settlements and notes that Icomb, Little Sodbury and Halford have been deleted from the list (although it is not clear when Halford had ever been listed or if this is a typo for Harford) (Hurst 1960, 1962a, 1962b).

By 1968 the list of deserted settlements had reached 67. A number of settlements do not appear in the 1968 Gazetteer that would be expected to have been identified at this point such as Middle Ditchford which is absent whilst Lower and Upper Ditchford both appear.

In 1980 Alan Saville published a list of deserted medieval village sites with earthworks in the Avon and Gloucestershire Cotswolds particularly those that were under threat of ploughing (Saville 1980). This listed a total of 43 settlements – of which 24 were on the 1968 Gazetteer. This did not include all the villages recorded in 1968 in this sub-region of Gloucestershire, but those that could be clearly identified on the ground. This results in 19 further sites being identified. In 1981 Mick Aston and Linda Viner published the first attempt at a list of the deserted settlements in Gloucestershire since the 1968 Gazetteer. This included settlements mentioned in Beresford (1954), Beresford and Hurst (1968), Saville (1980) as well as unpublished sites in the Medieval Village Research Group Archive, those that had been deleted from previous lists, and those in the records of Gloucestershire and District Archaeological Research Group. This list was not a definite list of known and tested sites, but was presented as a starting point for further investigation (Aston and Viner 1981). This included 173 sites, (14 from Beresford 1954 (including the deleted ones) and 66 from 1968 (Lark Stoke since having transferred to Warwickshire). By 1984 this list had risen to 195 (Aston and Viner 1984). Aston and Viner (1984) do suggest that many of the deserted settlements should not be called villages, lacking the size or criteria to be villages – such as a church. For the purposes of this website, many settlements have still been classed as deserted villages as opposed to deserted hamlets as the evidence would suggest a sizable population once inhabited the site, even if the settlement was subsidiary in status to another settlement.

Since these surveys much work has been carried out on individual sites but also on the wider context of settlements studies in the West Midlands. One researcher who has made a vital contribution to this study has been Christopher Dyer who has provided regional overviews (Dyer 1982, 2002) as well as in-depth studies of particular settlements (Aldred and Dyer 1991, Dyer 1987, 1998). In one of his earlier reviews of deserted settlements in the West Midlands he shows the range of reasons for desertion, and that on many occasions this is the result of long-term changes rather than sudden events, and the final abandonment of many settlements was after a slow gradual decline (Dyer 1982). These long-term affects often saw outward migrations from settlements and while accusations of forcible eviction were present there is also evidence of land owners trying to encourage tenants to stay by offering building repairs and support, or forcibly ensuring building maintenance (Dyer 1982: 28).

Within Gloucestershire there is a range of different landscape types which have seen different patterns of settlement development and desertion. This includes areas of nucleated settlement such as the Cotswolds as well as areas of very small hamlets and individual farms, which dominate the woodland areas of west Gloucestershire (Dyer 1987, 2002). One landscape that has been intensively studied has been that of the Cotswolds. Here a concentration of deserted sites has been identified (Dyer 1982). This shows the increase in the number of settlements identified since 1954 when Beresford stated ‘the Cotswolds have been remarkably free from depopulation’ (1954: 351). Traditionally the Cotswolds are seen as a pastoral landscape with nucleated settlements, but the medieval pattern was significantly different.

The nucleated villages of the Cotswolds were associated with high levels of arable agriculture and the development of open fields instead of the modern pastoral view (Dyer 1987). These settlements often show evidence of planning in their structure and layout. One suggestion for the organisation of settlements is the high proportion of slaves recorded at Domesday and the need to house these families close to their manorial centre (Dyer 1987, 2002). However this is not universally the case and some villages which on the outside look like a single planned unit may have actually had involved more than one landowner (Dyer 1987). On the Cotswolds nucleated villages were not the only the only form of settlement. Hamlets, mills, sheepcoates and granges were all present highlighting the presence of dispersed settlement intermingled with the nucleated villages (Dyer 2002). Some of the smaller settlements may have originated in areas heavily wooded, developing a dispersed pattern as small areas were gradually cleared (Dyer 2002).

On the Cotwolds there is a concentration of deserted settlements and a once packed landscape saw a reduction in settlements. Christopher Dyer provides a nice illustration of this when looking at one particularly deserted settlement – that of Lark Stoke. Here there are now only three villages in a 2 mile vicinity of the site, but at the height of settlement activity there had once been 11 villages and hamlets across the same area (Dyer 2012: 137). The Cotwolds seem to have been heavily affected by the crisis that developed in the fourteenth century. The Nonarum Inquisitiones for Gloucestershire shows that villages were starting to struggle in the mid-fourteenth century with at Harford and Ailworth recorded in 1341 that ‘many tenants left their holdings and left them vacant and uncultivated’ and at Littleton ‘seven parishioners of the hamlet of Littleton … abandoned their holdings and left the parish’ (Dyer 1982: 22). In total 17 parishes in Gloucestershire recorded tenants leaving and land being uncultivated (Dyer 2002). One suggestion Dyer puts forward to explain these struggles is the over-extension of arable farming and a shortage of livestock to help maintain soil fertility (Dyer 1982: 22). Long-term sustainability of the great number of settlements and such intensive arable agriculture was not possible and through much of the Cotswolds a decline in population is seen between 1300-1520 (Dyer 1987). Of the settlements that were struggling in the mid-fourteenth century, a number seem to be heavily affected by the time of the later fourteenth century, possibly compounded by the Black Death. Land that was gradually abandoned as villagers sought their fortunes elsewhere was then gradually enclosed. The conversion of land to pasture was recorded in the fifteenth century. In the 1480s John Rous published a list of 60 Warwickshire villages that he observed in ruins, some of which lie in modern Gloucestershire including the Ditchfords and Seizncote (Rous 1745, Dyer 1982). That a number of settlements were deserted and then put over to sheep farming is attested by the presence of sheepcotes over the earthworks at sites such as Manless Town, Pinnock, and Hilcot (Dyer 2002). These buildings would have been used to shelter sheep and from the excavated examples and documentary evidence seem to be common between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries and have gone out of use by the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Dyer 1995).

Excavations

Gloucestershire has seen a number of different projects investigating deserted settlement sites. The earliest excavation was in 1907 at Hullasey which identified two buildings and the possible location of the chapel (Baddeley 1910). In a more recent re-evaluation and survey of the site have suggested that this was in fact four buildings with over 30 buildings identified across the site (Ellis 1984).

Excavations at Old Sennignton in 1936 revealed stone walls and twelfth to fourteenth-century pottery but remains unpublished (Baldwin and O’Neil 1958). In 1962 trial trenches were placed across the settlement earthworks at Manless Town, partly to discover if any of the remains were Roman in date (Wingman and Spry 1993, Smith 1998). The results were not published at the time and recent discussion of the results shows different interpretations. Further field walking was undertaken at the site in 1992 which produced twelfth and thirteenth-century pottery (Smith 1998).

The most detailed work has been carried out at Upton under the leadership of Philip Rahtz between 1959 and 1968 as part of the courses taught at Birmingham University (Hilton and Rahtz 1966, Rahtz 1969, Watts and Rahtz 1984). This work focussed on detailed analysis of the earthworks, the excavation of a series of buildings in the centre of the site as well as a couple of small trial trenches across the settlement boundary and outlying buildings (Hilton and Rahtz 1966, Rahtz 1969). The survey identified at least 27 buildings, but the evidence from excavation suggests the number of buildings is probably greater as a single earthwork may hide a number of structures. The excavated building earthwork at the centre of the site revealed a series of stone buildings focused around two separate longhouses expanding and being adapted over time, preceded by timber structures (Hilton and Rahtz 1966, Rahtz 1969). The main building phases are suggested to be later twelfth to fourteenth century. Only a handful of finds can be dated to the fifteenth century and are nothing more than indications of people walking across the site. In 1973 a number of trenches were excavated across the site to improve the water supply and a watching brief conducted at the time recorded 49 features, and showed a number of features that were not visible on the earthwork plan of the site as well as buildings outside of the core of the settlement (Watts and Rahtz 1984).

Since this early work there have been no extensive excavations at any of other Gloucestershire site, but a number of detailed landscape and documentary surveys have added to our knowledge of settlement development and desertion. One long-term project investigated the landscape around Frocester starting in 1961 running up until 2009 (Price 2000a, 2000b, 2008, 2010). This took a long-term view and found evidence of a Roman villa under the medieval church. It has also clarified that the village of Frocester has a complex development, with a number of smaller farmsteads doted around the area and that the isolated church does not represent the location of the medieval settlement. This has now dismissed Frocester as a deserted medieval village, although added a number of smaller potential deserted sites.

A detailed study of the settlement history of the deserted settlement at Roel produced an interesting story of the difficulty of linking physical settlement evidence with the documentary record (Aldred and Dyer 1991). Earthworks at Roel Farm have been identified as the village of Roel, known from a range of documentary sources. However the earthworks are small in extent and the documentary evidence points to a sizable population with as many as 30 households in the early fourteenth century. The physical evidence at Roel Farm does not suggest many more than nine house plots. To the south of Roel Farm is the village of Hawling which was connected in a number of ways to Roel. On the northern side of Hawling are the earthworks of settlement remains and these had often been viewed as the shrunken settlement of Haweling. However the documentary evidence has confirmed this area once formed part of Roel village, named Roelside (Aldred and Dyer 1991). Further analysis of the documentary evidence shows that the split between the two areas of settlement, always recorded singularly as ‘Roel’ saw around a quarter of the population located at Roel and three quarters at Roelside, cheek by jowl with Hawling.

Other settlements where study since the 1968 Gazetteer has revealed detailed evidence of desertion include sites such as Little Aston (Dyer 1987). Here Dyer has shown the development of a small settlement and its relationship to the nearby Aston Blank. He has also shown the decline starting in the early fourteenth century and how one of the factors that led to desertion was the stress caused by the local miller, with outward migration from the settlement noted in 1340 when seven parishioners had left the parish (Dyer 1987). Little Aston fits into a landscape in the upper Windrush valley where another four deserted settlements are located (Aylworth, Castlett, Eyford and Harford) and where surviving settlements also show evidence of shrinkage such as at Temple Guiting and Aston Blank itself (Dyer 1987). Dyer has described the desertion in this landscape are ‘very severe, and began unusually early’ (Dyer 1987: 176).

At Taynton Parva survey by the local archaeological group has brought some clarity to the plan of the earthworks at this complex site, but the exact layout of the settlement is still unclear (Williams 1996). A number of other sites have been studied as part of larger projects. Lark Stoke has been investigated as part of the Admington Survey looking at the development and decline of three neighbouring villages (Dyer 1998). The rise and fall of Thornden is discussed by Dyer in his consideration of hamlets and dispersed settlement in the Cotswolds (2002).

County Boundaries

The boundaries of Gloucestershire have seen many changes, particularly in areas neighbouring Warwickshire and Worcestershire. There have also gains and losses with Oxfordshire, Somerset, Wiltshire and Herefordshire. This can make tracking the documentary history of some settlements quiet difficult.

Documentary Evidence

A Lay Subsidy Roll of 1327 exists for Gloucestershire, listing not only the payments made, but the names of the individuals charged (Franklin 1993). The 1327 Lay Subsidy was levied at one-twentieth of a person’s movable wealth for those with at least 10s in possessions (Franklin 1993). The number of payers has been included in the description for each settlement but for further details you should refer to Franklin (1993). The Lay Subsidy of 1334 is complete for Gloucestershire but includes 29 places now in different counties and there are 27 places that are in the 1974 county of Gloucestershire recorded in other counties (Glasscock 1975: 90). No records for the 1377 Poll Tax survive and only a single list recording four places survives for the 1379 Poll Tax (Fenwick 1998: 249). Although there is some damage to the rolls there seems to be a complete set of returns for the 1381 Poll Tax in a number of the Gloucestershire hundreds but not for the county as a whole (Fenwick 1998: 248). In the 1524 and 1525 Lay Subsidies there are a number of settlements that appear for the first time and this has been explained by the survey of 1334 including smaller settlements under larger central settlements (Sheail 1998: 91). The survival of the sixteenth-century Lay Subsidies is variable, and no transcription of the 1543 Subsidy is available (Sheail 1998: 91). The 1563 Diocesan Returns survives in copy form, and the 1603 is also available (Dyer and Palliser 2005: 154).

County Records

Two Historic Environments Records cover the area of Gloucestershire. The Gloucestershire HER is based in Gloucestershire County Council and their record can be accessed via HeritageGateway. The South Gloucestershire HER is based in South Gloucestershire Council and is currently not available online. Gloucestershire Archives have a useful online search facility.

Much of the work undertaken in Gloucestershire has been published by the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society and their Transactions can be accessed online via their website allowing many of the key articles referenced here to be freely available.

References

Aldred, C. and C. Dyer 1991. ‘A Medieval Cotswold Village: Roel, Gloucestershire’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 109: 139-170.

Aston, M. and L. Viner 1981. ‘Gloucestershire Deserted Villages’, Glevensis 15: 22-29.

Aston, M. and L. Viner 1984. ‘The Study of Deserted Villages in Gloucestershire’, in A. Saville (ed.) Archaeology in Gloucestershire: 276-293. Cheltenham: Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museums and Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society.

Baldwyn, R.C. and H.E. O’Neil 1958. ‘A Medieval Site at Chalk Hill, Temple Guiting, Gloucestershire, 1957’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 77: 61-65.

Baddeley, W. St C. 1910. ‘The Manor and Site of Hullasey, Gloucestershire’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 33: 338-354.

Beresford, M.W. 1954. The Lost Villages of England. London: Lutterworth.

Beresford, M.W. and J.G. Hurst (eds) 1971. Deserted Medieval Villages: Studies. London: Lutterworth Press.

Dyer, A. and D.M. Palliser 2005. The Diocesan Population Returns for 1563 and 1603. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dyer, C. 1982. ‘Deserted Medieval Villages in the West Midlands’, Economic History Review 35:19-34.

Dyer, C. 1987. ‘The Rise and Fall of a Medieval Village: Little Aston (in Aston Blank), Gloucestershire’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 105: 165-182.

Dyer, C. 1995. ‘Sheepcotes: Evidence for Medieval Sheepfarming’, Medieval Archaeology 39: 136-164.

Dyer, C. 1998. ‘Medieval Pottery from the Admington Survey: Some Preliminary Conclusions’, Medieval Settlement Research Group Annual Report 13: 24-25.

Dyer, C. 2002. ‘Villages and Non-Villages in the Medieval Cotswolds’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 120: 11-35.

Dyer, C. 2012. A Country Merchant, 1495-1520: Trading and Farming at the End of the Middle Ages. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, P.J. 1984. ‘The Medieval Settlement at Hullasey, Coates’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 102: 210-211.

Fenwick, C.C. 1998. The Poll Taxes of 1377, 1379 and 1381: Part 1: Bedfordshire-Leicestershire. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Franklin, P. 1993. The Taxpayers of Medieval Gloucestershire. Stroud: Alan Sutton.

Glasscock, R.E. 1975. The Lay Subsidy of 1334. London: Oxford University Press.

Hilton, R.H. and P.A. Rahtz 1966. ‘Upton, Gloucestershire, 1959-1964’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 85: 70-146.

Hurst, J.G. 1960. ‘Appendix C. Gloucestershire: Revised D.M.V. List 1959’, Deserted Medieval Village Research Group Annual Report 8.

Hurst, J.G. 1962a. ‘Appendix A. List of the Deserted Medieval Villages Identified Since the Publication of Lost Villages of England in 1954 and December 1962’, Deserted Medieval Village Research Group Annual Report 10.

Hurst, J.G. 1962b. ‘Appendix B. List of sites deleted from ‘The Lost Villages of England’ between 1954 and 1962’, Deserted Medieval Village Research Group Annual Report 10.

Price, E. 2000a. Frocester: a Romano-British settlement, its antecedents and successors. Volume 1 the sites. Stonehouse: Gloucester and District Archaeological Research Group.

Price, E. 2000b. Frocester: a Romano-British settlement, its antecedents and successors. Volume 2: the Finds. Stonehouse: Gloucester and District Archaeological Research Group.

Price, E. 2008. Frocester: a Romano-British settlement, its antecedents and successors. Volume 4: The Village. Stonehouse: Gloucester and District Archaeological Research Group.

Price, E. 2010. Frocester: a Romano-British settlement, its antecedents and successors. Volume 3: Excavations 1995-2009. Stonehouse: Gloucester and District Archaeological Research Group.

Rahtz, P.A. 1969. ‘Upton, Glos., 1964-68’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 88: 74-126.

Rous, J. 1745. Historia Regum Angliae. Oxford.

Saville, A. 1980. Archaeological Sites in the Avon and Gloucestershire Cotswolds. Bristol: Committee for Rescue Archaeology in Avon, Gloucestershire and Somerset.

Sheail, J. 1998. The Regional Distribution of Wealth in England as Indicated in the 1524/5 Lay Subsidy Returns: Volume One. London: List and Index Society.

Smith, N. 1998. ‘Manless Town, Brimpsfield: An Archaeological Survey’, Glevensis 31: 53-58.

Watts, L. and P. Rahtz 1984. ‘Upton Deserted Medieval Village, Blockley, Gloucestershire, 1973’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 102: 141-154.

Williams, S.E. 1996. Taynton Parva Deserted Medieval Village. Its History and Archaeology. Lydney: Dean Archaeological Group Occasional Publication No. 2.

Wingham, H. and N. Spry 1993. ‘More Recent Views on Manless Town, Brimpsfield SO 928 116’, Glevensis 27: 26-32.

List of deserted villages recorded in 1968

List of deserted villages recorded in 1968

Site names in italics are unlocated and so do not appear on the VIllage Explorer. For the unlocated sites, click on their names and it will take you to the basic information about this village.

- Abloads Court

- Alkington

- Ampney St. Mary

- Aston

- Aylworth

- Bidfield

- Boxwell

- Brickhampton

- Castlett Farm

- Charlton

- Coberley, Upper

- Combe End

- Daylesford

- Didcot

- Ditchford, Lower

- Ditchford, Upper

- Elmstree

- Eyford

- Farmcote

- Frampton

- Frocester

- Gawcombe

- Harford

- Pontune

- Postlip

- Prescott

- Roel

- Sapletone

- Sennington

- Sezincote

- Shipton Solars

- Slad

- Stockwell

- Stonehouse

- Stowell

- Sudeley

- Taynton Parva

- Uletone

- Upcote

- Upton

- Wall

- Williamstrip

- Wormington Dastyn

- Wormington Parva