Description

Buckinghamshire has an early listing of deserted settlements appearing as an appendix to a paper by Maurice Beresford on glebe terriers and open-field systems in 1954 (Beresford 1953-4). This list contained 29 settlements with another 14 suspected sites – all of the 29 settlements apart from Bourton are still listed in 1968, and 11 of the suspected sites also make the Gazetteer. At the same time, when he published Lost Villages of England, Beresford (1954, 339-343) listed 30 settlements, with 12 suspected sites, so 42 in total, one less than the other list. The extra accepted site was Filgrave (which is absent from the Gazetteer by 1968). The two suspected sites that have dropped off the list are Averingdon and Helsthorpe.

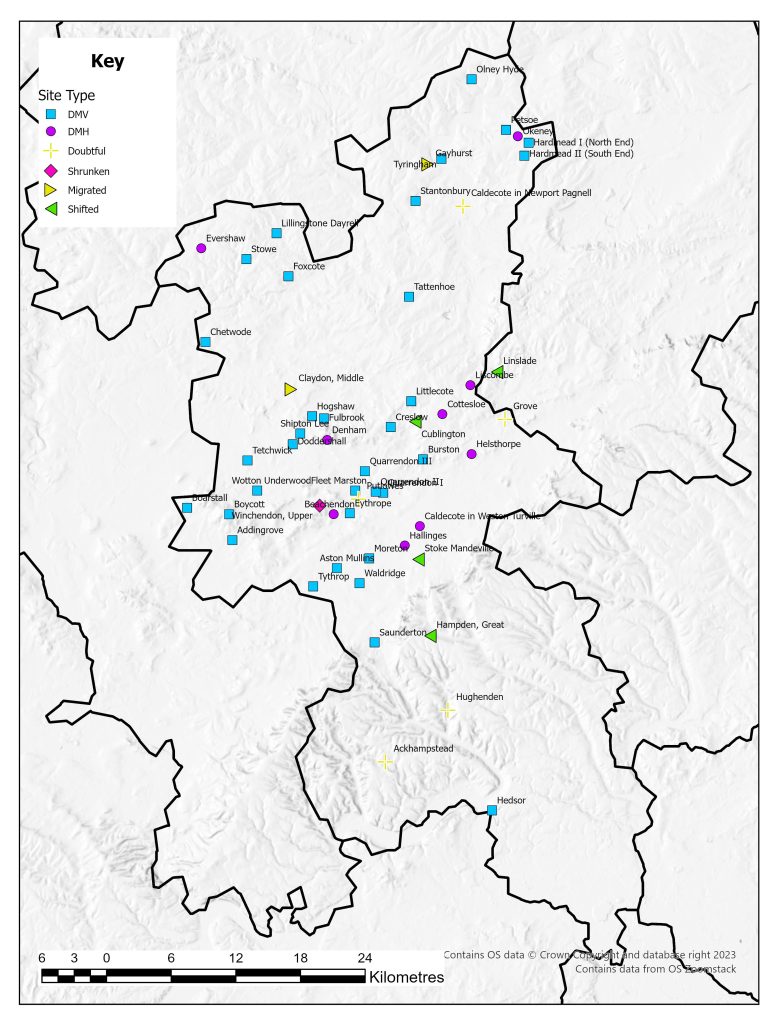

There were 56 settlements listed in the 1968 Gazetteer, and since this time the number has grown. Page has highlighted this stating the 56 in 1968 became 60 by 1979, and 83 by 1997 (Page 2005 189). This increase in numbers is set upon a backdrop of large regional surveys such as that carried out on the medieval settlement of the East Midlands and the Whittlewood region as well as more focused research on specific sites in the county (Lewis et al. 2001, Jones and Page 2006). This research paints a vivid picture of a diverse range of settlements and an equally diverse set of events that leads to settlement desertion. This includes the rare occasion of a dated desertion for the settlement at Boarstall which was depopulated at the end of the first week of June 1645 as part of the turmoil of the Civil War (Porter 1984).

Buckinghamshire also affords the opportunities of studying an area of contrasting landscapes that have resulted in different forms of settlement pattern (Taylor-Moore 2007: 2). The county straggles the boundary between two landscape character zones – the Central Province to the north and the South-Eastern Province to the south (Roberts and Wrathmell 2000). The Central Province is characterised by nucleated villages and open-field systems and the South-East province is were dispersed settlement dominates. This is a very broad division, and on a more local basis there is much regional diversification (Taylor-Moore 2007: 2). For example the work around Milton Keynes has identified polyfocal settlement to the west of the city whereas nucleated settlements were found elsewhere (Ievns et al. 1995: 211). These two landscapes have formed for a variety of reasons but they also mark the changes in geology and soils with claylands to the north and a chalk landscape to the south (Reed 1979: 26). The majority of the deserted settlements in the 1968 Gazetteer can be found in the north of the county, on the claylands.

Excavations

A number of settlements have been subjected to excavations as part of the development of Milton Keynes and it ongoing expansion. Tattenhoe was one such settlement (Ivens et al. 1995). The development of the city also affected sites that were not on the Gazetteer including Westbury-by-Shenley (SP 829356, north of Shenley Brook End, refereed to on some records by this name) (Ivens et al. 1995). Rescue excavations at Stantonbury ahead of quarrying amounted to little more than rapid recording of disturbed archaeology but revealed house platforms and pottery dating from the twelfth to fourteenth centuries (Mynard 1971). Excavations have also revealed evidence of a deserted settlement that could also be called a ‘pottery production centre’ at Olney Hyde (Mynard 1984: 56).

The landscapes of Quarrendon and Hardmead have both been subjected to more detailed survey and analysis and show the complexity of settlement in Buckinghamshire (Everson 2001, Smith 1985). Both these sites demonstration the polyfocal nature of the settlement with clusters of dwellings joined together – sometimes over quiet a distance to form a single settlement unit.

County Boundaries

Buckinghamshire is one of the smaller English Counties. It has both gained and lost land to Berkshire and Oxfordshire in the past. The area is now divided between the County of Buckinghamshire and the unitary authorities of Milton Keynes and Slough.

Documentary Evidence

The original 1334 record is not complete for the county, but has been supplemented with details from 1336 as these have been shown to be based on the 1334 Subsidy (Glasscock 1975). A number of places recorded in Buckinghamshire in 1334/1336 since transferred to Oxfordshire (pre-1974) and a number of places in Buckinghamshire pre-1974 are recorded in Oxfordshire in 1334/1336 (Glasscock 1975). There is no complete set of records for any of the fourteenth-century poll taxes. In 1377 there is only surviving records for the Chiltern hundreds of Stoke, Burnham and Desborough. In 1379 only the returns for the Aylesbury Hundred survives. There are no surviving returns for 1381 (Fenwick 1998: 62). For the sixteenth-century lay subsidies there are records for the entire county, but some of the 1525 records are defective (Sheail 1998: 66). The numbers of the 1543 Lay Subsidy are sometimes supplemented with those from 1544 or 1545 if they are missing. The 1563 Diocesan return survives with the returns for the Diocese of Lincoln (Dyer and Palliser 2005: 175).

County Records

Two HERs cover the area of the county, Buckinghamshire HER (based at Buckinghamshire County Council) and Milton Keynes HER (based within Milton Keynes Council) Both are available to search via Heritage Gateway and the records for Buckinghamshire include an excellent selection of photographs.

References

Beresford, M.W. 1953. ‘Glebe Terriers and Open-Field Buckinghamshire: with a Summary List of Deserted Villages of the County’, Records of Buckinghamshire 16: 5-28.

Beresford, M.W. 1954. The Lost Villages of England. London: Lutterworth Press.

Everson, P. 2001. ‘Peasants, Peers and Graziers: the Landscape of Quarrendon, Buckinghamshire, Interpreted’, Records of Buckinghamshire 41: 1-46.

Ivens, R., P. Busby and N. Shepherd 1995. Tattenhoe and Westbury: Two Deserted Medieval Settlements in Milton Keynes. Aylesbury: Buckinghamshire Archaeological Society Monograph Series no. 8.

Jones, R. and M. Page 2006. Medieval Villages in an English Landscape. Macclesfield: Windgather Press.

Lewis, C., P. Mitchell-Fox and C. Dyer 2001. Village, Hamlet and Field: Changing Medieval Settlements in Central England. Macclesfield: Windgather Press.

Mynard, D.C. 1971. ‘Rescue Excavations at the Deserted Medieval Village of Stantonbury Bucks’, Records of Buckinghamshire 19: 17-41.

Mynard, D.C. 1984. ‘A Medieval Pottery Industry at Olney Hyde’, Records of Buckinghamshire 26: 56-85.

Page, M. 2005. ‘Destroyed by the Temples: the Deserted Medieval Village of Stowe’, Records of Buckinghamshire 45: 189-204.

Porter, S. 1984. ‘The Civil War Destruction of Boarstall’, Records of Buckinghamshire 26: 86-91.

Reed, M. 1979. The Buckinghamshire Landscape. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Roberts, B.K. and S. Wrathmell 2000. An Atlas of Rural Settlement in England. London: English Heritage.

Smith, P.S.H. 1985. ‘Hardmead and its Deserted Village’, Records of Buckinghamshire 27: 38-52.

Taylor-Moore, K. 2007. Solent Thames Historic Environment Research Framework: Resource Assessment: Medieval Buckinghamshire (AD 1066-1540). Unpublished Report.

List of deserted villages recorded in 1968

- Ackhampstead

- Addingrove

- Aston Mullins

- Beachendon

- Boarstall

- Boycott

- Burston

- Caldecote in Newport Pagnell

- Caldecote in Weston Turville

- Chetwode

- Claydon, Middle

- Cottesloe

- Creslow

- Cublington

- Denham

- Doddershall

- Evershaw

- Eythrope

- Fleet Marston

- Foxcote

- Fulbrook

- Gayhurst

- Grove

- Hallinges

- Hampden, Great

- Hardmead I (North End)

- Hardmead II (South End)

- Hedsor

- Helsthorpe

- Hogshaw

- Hughenden

- Lenborough

- Lillingstone Dayrell

- Linslade

- Liscombe

- Littlecote

- Moreton

- Okeney

- Olney Hyde

- Petsoe

- Putlowes

- Quarrendon I

- Quarrendon II

- Quarrendon III

- Saunderton

- Shipton Lee

- Stantonbury

- Stoke Mandeville

- Stowe

- Tattenhoe

- Tetchwick

- Tyringham

- Tythrop

- Waldridge

- Winchendon, Upper

- Wotton Underwood