Description

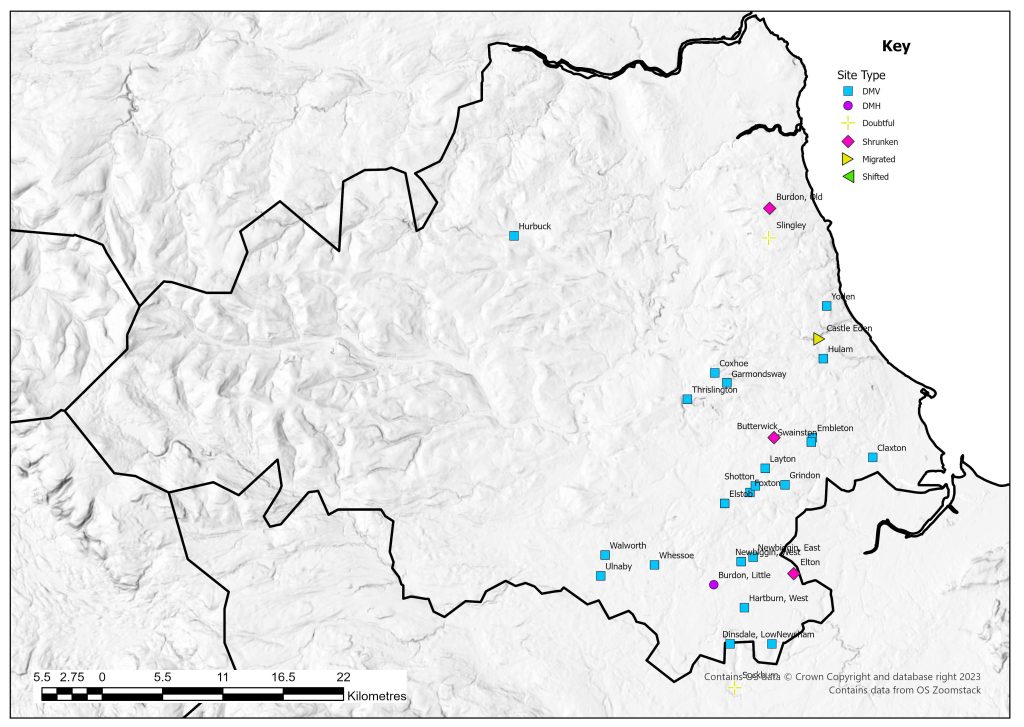

In 1954 seven villages were suggested as classic deserted sites with another nine listed as possibilities (Beresford 1954: 350). One site, Newton – Archdeacon does not appear on the 1968 Gazetteer, which lists a total of 29 sites. Extensive work has since been carried out in the county and the HER now records over 140 sites. Much of the work has been spearheaded by Brian Roberts’ analysis of village form. Evidence from such settlement investigation in the county and the wider northern England has highlighted that up to 80% of settlements contain evidence of planning in their structure and layout (Roberts 2008, Wrathmell 2012). There are a range of plans that these settlements follow – but many of the settlements listed on this website show clear evidence of the regular two-row format, with the rows facing each other, often on either side of a street or a green. A more complex regular plan can be seen at Walworth which shows evidence of two regular rows to the north and west of a central green, with perhaps further evidence for more tofts on the other sides.

There is a change in settlement pattern in County Durham from east to west, with the east falling within the landscape characterised by nucleated villages. To the west is an increase in farmsteads and a more dispersed settlement pattern with place-names signifying woodland. This is mainly located on Pennine Spurs and High Pennines (Roberts 2008, Roberts et al. 2005). The general pattern of desertions in the county have been studied from a number of different angles and suggest gradual reductions rather than sudden desertions (Roberts 2008: 44).

Excavations

Compared with some of the other counties there has been considerable fieldwork on deserted sites in County Durham. In several cases this was due to an imminent threat to the archaeology. One of the earliest excavations was undertaken at Yoden, a site now identified as Horden (Middleton 1885, Turnbull 2006). Excavations in 1884 proved the medieval date of the remains uncovering what were described as ‘foundations of the rudest descriptions, consisting entirely of mere shapeless masses of un-hewn stone’ (Middleton 1885: 186). Since then the site has been encroached upon by Peterlee but a small area of earthworks still survive (Turnbull 2006).

At Swainston at least 10 house sites have been identified and two of these were excavated between 1957-1960 (Booth 1957). The excavated houses were located in the south-east of the site and may have been on the edge of the settlement. Both structures have been dated to the fourteenth to fifteenth century (Wilson and Hurst 1960: 160). A full excavation report has not appeared.

Excavations were conducted in the 1960s at West Hartburn. Earthworks north of the road through the village had been ploughed and the excavations concentrated on the earthworks that still existed to the south (Still and Palliser 1964, 1967, Palliser and Wrathmell 1990). These revealed evidence of a number of different buildings with at least two longhouses uncovered, and a smaller building which is now thought to be a smaller structure associated with one of the longhouses. It is estimated that altogether there were 12 tofts. Pottery dating to the thirteenth to sixteenth century was recovered (Palliser and Wrathmell 1990).

The remains of the village of Thrislington were badly damaged during quarrying activity; however rescue excavations were undertaken in 1973-1974 (Austin 1989). These excavations revealed evidence of toft boundaries, a chapel, industrial areas, houses and a manor house. The east-west track present in the 1970s signified the medieval routeway through the settlement and on either side of this were enclosures which backed onto ridge and furrow. These enclosures seemed to represent tofts with building platforms to the front of them. The excavations suggested the manor house was constructed in the twelfth century and abandoned in the early fourteenth century. Excavation of buildings in the tofts suggests they appear in the thirteenth century and some disappear by the middle of the fifteenth century, while others continue until the sixteenth century (Austin 1989).

Excavations were carried out at Castle Eden in 1974 when the site was under threat from development (Austin and O’Mahoney 1987). The earthworks at the site were not clear, but ten trenches were excavated down to the first archaeological features, but not fully excavated (Austin and O’Mahoney 1987). The intention was to show the presence of medieval settlement and the potential of the site while not compromising the archaeology. These revealed a north-south hollow way and suggested houses to either side forming two rows. Pottery uncovered dated from the twelfth to sixteenth century (Austin and O’Mahoney 1987).

A deserted settlement in County Durham has also featured on Channel 4’s Time Team in 2008. Survey work and excavations as part of the programme suggested that the settlement was only occupied for a short period of time from the late thirteenth century to the fifteenth century (Wessex Archaeology 2008). A survey in 2007 had suggested that there was an earlier phase to the site without a green (Grindley et al. 2008). The small-scale excavation though did not support this conclusion (Wessex Archaeology 2008).

One site, Sockburn, is currently under investigation due to the presence of a possible minster church and pre-conquest sculpture (Semple and Petts 2014). It is in doubt if there was ever a village here, but this project may help resolve this issue.

Smaller excavations have occurred elsewhere such as at Elton where a medieval barn was uncovered (Nenk et al. 1992). Some sites have also undergone detailed survey work. One such site is Newsham which was surveyed in 1972. The earthworks could be seen clearly from the air, located to the east and north of the River Tees. These included hollow ways and enclosures. At least 11 tofts were identified and at least 11 building platforms suggested including one that was possibly the chapel of St James (Pallister and Pallister 1978). These were aligned along a north-south axis which corresponded to the modern farm track, and the house plots were located

County Boundaries

There have been few changes to the county boundary with some land being lost to the North Riding of Yorkshire. Today County Durham covers much of the central and western parts of the county with the Boroughs of Gateshead, South Tyneside, Sunderland, Hartlepool, Stockton on tees (part also in North Riding of Yorkshire) and Darlington.

Documentary Evidence

This area was not included in the Domesday Book. The first record of much of the land is the Bolden Book commission in 1183 recording the landholdings of the Bishop of Durham (Austin 1982). It is suggested that that some entries are for nucleated settlement, in others they indicate the landholdings of an individual across an area of dispersed settlement. The palatine of Durham was exempt from much medieval taxation so therefore there is no 1334 record and it has been left blank on the website. In 1377 no writ was issued for the Poll Tax. In 1379 commissions were supposed to levy the tax and unlike Chester this was not cancelled but no payment was made in 1379 or 1381 (Fenwick 1998: xxi). Again in the sixteenth century no Lay Subsidy was required in 1524, 1525 or 1543 (Sheail 1998: 3). The Diocesan Return of 1563 survives intact.

County Records

Three HERs cover this region. That for Durham HER covers Durham County Council and Darlington Borough and is available online via the Keys to the Past website. Tyne and Wear HER which covers Gateshead, South Tyneside and Sunderland is available via Heritage Gateway. The Tees Archaeology HER that covers Hartlepool and Stockton on Tees is currently not available online.

References

Austin, D. 1982. Bolden Book Northumberland and Durham. Chichester: Phillimore.

Austin, D and C. O’Mahoney 1987. ‘The Medieval Settlement and Landscape of Castle Eden, Peterlee, Co. Durham: Excavations 1974’, Durham Archaeological Journal 3: 57-78.

Austin, D. 1989. The Deserted Medieval Village of Thrislington, Co Durham: Excavation 1973-1974. London: Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph Series No 12.

Beresford, M.W. 1954. The Lost Villages of England. London: Lutterworth.

Booth, J.C. 1957. ‘Swainston Village’, South Shields Archaeological and History Society Papers 1, 5: 9-14.

Fenwick, C.C. 1998. The Poll Taxes of 1377, 1379 and 1381: Part 1: Bedfordshire-Leicestershire. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grindey, C., M. Jecock and A. Oswald 2008. Ulnaby, Darlington: An Archaeological Survey and Investigation of the Deserted Medieval Village. English Heritage Unpublished Research Department Report No. 13-2008.

Middleton, R.M. 1885. ‘On Yoden, A Medieval site between Castle Eden and Easington’, Archaeologia Aeliana 10: 186-187.

Nenk, B.S., S. Margeson and M. Hurley 1992. ‘Medieval Britain and Ireland in 1991’, Medieval Archaeology 36: 204-205.

Pallister, A. and S. Wrathmell 1990. ‘The Deserted Village of West Hartburn, Third Report: Excavations of Site D and Discussion’, in B.E. Vyner (ed.) Medieval Rural Settlement in North-East England: 59-78. Durham: Architectural and Archaeological Society of Durham and Northumberland Research Report 2.

Pallister, A.F. and P.M.J. Pallister 1978. ‘A Survey of the Deserted Medieval Village of Newsham’, Transactions of the Architectural and Archaeological Society of Durham and Northumberland 4: 7-19.

Roberts, B.K. 2008. Landscapes, Documents and maps: Villages in Northern England and Beyond AD 900-1250. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Roberts, B.K., H. Dunsford and S.J. Harris 2005. ‘Framing Medieval Landscapes: Region and Place in County Durham’, in C.D. Liddy and R.H. Britnell (eds) North-East England in the Later Middle Ages: 221-237. Woodbridge: Boydell.

Semple, S and D. Petts 2014. Sockburn Project, Co Durham. https://www.dur.ac.uk/archaeology/research/projects/?mode=project&id=716

Sheail, J. 1998. The Regional Distribution of Wealth in England as Indicated in the 1524/5 Lay Subsidy Returns: Volume One. London: List and Index Society.

Still, L. and A. Paliister 1964. ‘The Excavation of One House Site in the Deserted Village of West Hartburn, County Durham’, Archaeologia Aeliana 42: 187-206.

Still, L. and A. Pallister 1967. ‘West Hartburn 1965 Site C’, Archaeologia Aeliana 45: 139-148.

Turnbull, P. 2004. A Deserted Medieval Village off Eden Lane, Peterlee, Co. Durham. The Brigantia Archaeological Practice Unpublished Report.

Wessex Archaeology. 2008. Ulnaby Hall, High Coniscliffe, County Durham: Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results. Wessex Archaeology Unpublished Report 68731.01.

Wilson, D.M. and J.G. Hurst 1960. ‘Medieval Britain in 1959’, Medieval Archaeology 4: 134-165.

Wrathmell, S. 2012. ‘Northern England: Exploring the Character of Medieval Rural Settlements’, in , in N. Christie and P. Stamper (eds) Medieval Rural Settlement in Britain and Ireland AD 800-1600: 249-269. Oxford: Windgather.

List of deserted villages recorded in 1968

- Burdon, Little

- Burdon, Old

- Butterwick

- Castle Eden

- Claxton

- Coxhoe

- Dinsdale, Low

- Elstob

- Elton

- Embleton

- Foxton

- Garmondsway

- Grindon

- Hartburn, West

- Hulam

- Hurbuck

- Layton

- Newbiggin, East

- Newbiggin, West

- Newsham

- Shotton

- Slingley

- Sockburn

- Swainston

- Thrislington

- Ulnaby

- Walworth

- Whessoe

- Yoden